Bagru, India – On the edge of the Thar desert in Rajasthan, where time moves slowly and to a rhythm of tradition, lies the town of Bagru. This isn’t just any Rajasthani village; it’s a living craft museum and a sprawling textile bazaar where the ancient craft of Dabu block printing has thrived in the Chhippa community for centuries.

In the narrow, dusty streets lined with shops, workshops, and block print studios, artisans transform meters of fabric into works of printed art. Skilled hands have passed down the knowledge of heritage crafts, surface design secrets, printing methods, and secret mud paste recipes through many generations.

My journeys to Bagru are always more than just a trip—they are life lessons learned with every taxi ride back to Jaipur. Each journey allows for reflection, and the vistas through the car windows inspire ideas and countless more textile journeys.

Every ride into this village, passing camels, cows, jeep taxis, loaded buses, and multicoloured trucks with tassels and loud tooters, takes me deep into a world of textiles. The early morning road trips on Sundays are the best; the streets are quieter than usual, allowing for a more serene experience.

I always look forward to each taxi ride, feeling blessed to learn from the masters and to speak the language of patterns, pigments, and prints—a language they learned by practicing and following family traditions.

The Rhythm of Time

Setting foot in Bagru introduces you to a rhythm of time unlike any other. The town’s rustic charm lies in its busy streets, lanes, shops, and workshops that snake through the village. The roads get crowded, and the air is filled with dust and the earthy scent of clay and natural dyes, a sensory reminder that in Bagru, nature and craft are one.

Bagru is much larger than it initially appears, stretching far and wide. With each visit, I discover new streets and corners, making it feel even larger. I still find it hard to orient myself and am not sure if I will ever have the confidence to drive from Jaipur to Bagru by myself. However, I have faith in the skills of the drivers who take me on these journeys.

The road between Jaipur and Bagru is a world of its own—a kind of madness that becomes a symphony of chaos. Many of the buildings and shops toward the center of town double as printing workshops and studios of artisans. Some of these buildings are centuries old, carrying the weight of history within their walls.

I was fortunate to have Avinash, one of my Dabu block print teachers, take me to one of the oldest print shops in town. We accessed this sacred space through a heavy wooden door with a rusted lock. The building still stands, but the inside is covered in dust, with relics of the craft scattered in the tiny rooms, each carrying a piece of history.

The abandoned printers workshop is in the image on the left. From the outside, this building appears abandoned, easily overlooked by passersby. Avinash, my teacher, took me on an electric scooter ride through the village, weaving through time and history. This is the entrance to the oldest block print studio in Bagru—a place once alive with craftsmanship, now standing deserted. Considered unsafe to enter, the building remains locked and inaccessible to the public. Photo Lizane Louw

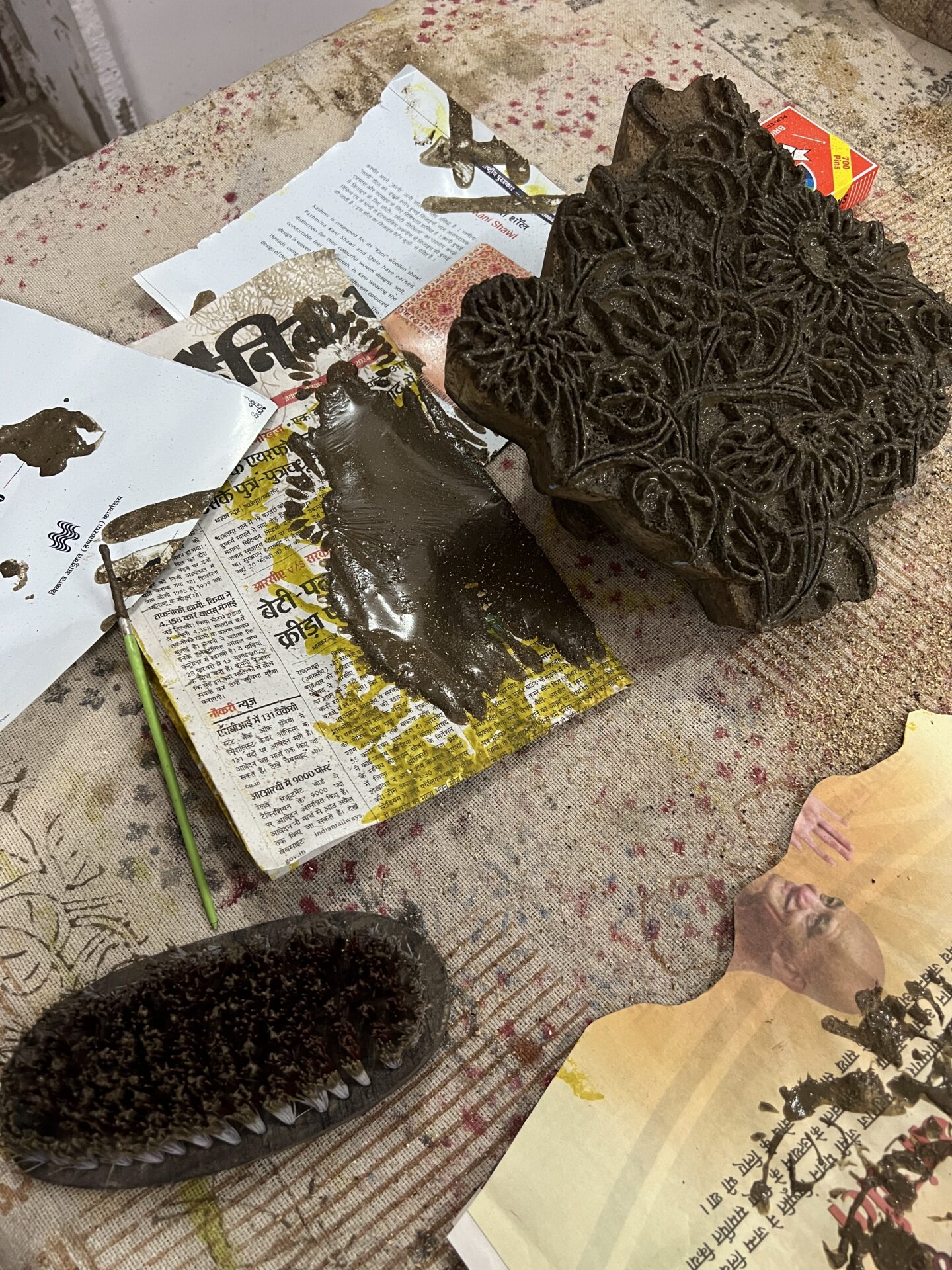

An old block used for Dabu mud printing on the right—a relic from a bygone era. I found this hand-carved woodblock in a deserted building, the block a silent reminder of a time when this print shop thrived. The artisans who once worked here printed textiles for the patrons of the craft, including the Rajputs, local merchants, and the surrounding community. Today, the building stands empty, its history traced into every pattern and used block. Photo Lizane Louw

Dabu Block Printing: Earth and Traditional Artistry

The Dabu block printing process begins with fabric preparation, like most hand-print traditions. Most workshops I attended in Bagru followed the same traditions: cotton is washed to remove impurities and starch from the fabric. After scouring, the fabric is laid out to dry under the desert sun. I always spend a few days with a studio for workshops, and I have had some great “village tours” around Bagru. Watching the textiles being placed in the sun is always striking, highlighting how much the elements of nature are used in the production cycle of these printed cloths.

A woman in Bagru carefully lays out scoured fabric under the sun, a crucial step in the Dabu printing process. Before any patterns are printed or dyes are applied, the fabric must be thoroughly cleaned and sun-dried to absorb the natural dyes evenly. Her work is an essential foundation of this centuries-old craft, connecting tradition, skill, and sustainability in every piece of cloth. Photos Lizane Louw

When the fabric is dry, it is ready for printing. The cloth is laid out on unique print tables prepared with layers of jute and cotton. Once the fabric is placed and pinned to the table, it is ready to be printed.

The mud paste is a resist made from clay, gum, and lime, known as ‘Dabu.’ This is where the real magic begins for me. It’s incredible how each family or small craft business has its own recipes and experiments, making the best print pastes I have ever printed with.

On the left is a mud tray prepared for the Dabu printing for sample prints at Jait Textart. On the right are some of the tools I used for the sample prints I printed for my first collection with Mud and Water in Bagru. Photos Lizane Louw

I attended many Bagru and Dabu block print workshops and learned inspiring techniques from master artisans. Besides getting my hands dirty with mud and creating textile art, I enjoy observing them practising their craft. I have come to learn that a master printer’s skill is evident in the rhythm with which they print and how they handle the blocks. I have seen incredible work and learned so much with each visit.

The mud paste has a distinct smell, and the workshops and print studios have a particular scent. This is one of the reasons I am so drawn to the craft; it is so earthy and raw.

I love how this process of Dabu printing challenges me to think in the negative when I print a design. You have to see the design you are printing “inverse,” as the paste blocks out the patterns that would not be dyed.

I admire the artisans applying the paste using carved wooden blocks every time I observe them. The precision and artistry required to create these beautiful mud cloths come from years of practice. It is not an easy job and is very time-consuming. I also love how most of the prints made with Dabu are more earthy, raw, and geometrical; it is not as fine as work from the Bagru print tradition.

Each block, carved with designs used for generations, is pressed onto the fabric, leaving behind a pattern that will resist the dye in the next step. There is a distinct sound when you remove the block from the cloth after you make an imprint; it is almost like a “thleeeup” sound, resembling the noise of tape slowly peeling off a surface or squeezing wet mud through your fingers. It can get messy.

On the left, with precision, patience and an eye for detail, a Dabu block print artisan in Bagru prints mud resist onto fabric, preparing it for dyeing. On the right, a master printer carefully stamps the Dabu resist, ensuring each imprint forms part of the intricate design. Photos Lizane Louw

After the fabric is printed, sawdust is dusted over the fabric to set and secure the print in place and to help with the drying process. This allows the print to set and not run. The printed work is then laid outside the studios and workshops to dry in the hot desert sun. Once the mud has dried, the fabric is dyed using natural colors derived from plants and minerals.

I have seen and experienced the vats in Bagru and learned about the traditions of creating these beautiful natural palettes that work with Dabu. Indigo for blues, turmeric for yellows, turmeric and indigo for green, or indigo pomegranate for deeper forest greens, and as the locals call it, Kashish (natural iron deposit) for grey or brown. Pomegranate and alum are also historically used to make red prints—each color is solid, vibrant, and very earthy, reflecting the natural elements from which they are sourced.

Once dyed, the resist paste forms the pattern, and the design is revealed when the fabric is removed from the dye bath. After washing in water baths, the resist paste creates the final intricate patterns. The result is a piece of mud cloth that is not just beautiful but carries the soul of Bagru. Each printed piece is one of a kind; no two designs or prints are ever the same. The elements of nature play a part in creating these stunning pieces. The quality of the water also affects the color of the prints.

What I found most interesting is how the seasons and the sun also play a part in the final print of the Dabu block print design. In the winter, the prints are more defined and crisp; in the summer, when the sun bakes down on the earth, the mud dries faster and cracks, creating a new look of marbling and a new feeling to the printed cloth. I find this fascinating; nature truly creates art.

The hand motions when printing with mud in the Dabu tradition and Bagru tradition with natural inks are different. You handle the blocks differently. Those gentle movements, with each tradition, help you create the prints. With Dabu printing, it is more of a slide motion when you remove the block from the mud print. I like the rhythm and the sound of mud printing; it stuck with me.

My efforts with my first mud prints were clumsy and uneven; I can see it now. I know what I am looking at and where I made mistakes. To to master this craft, skill and patience are required. I fell deeply in love with the Dabu print tradition, and I will continue to research and write about this craft that has taught me so much.

Sustainability and Dabu Block Printing

In a world dominated by fast fashion and trends, Dabu printing is probably one of the best examples of sustainability in textile printing that I have come across. The process is eco-friendly, from using mud and natural dyes to carefully managing water resources. I think this is slow textile crafts and a form of slow fashion in its purest form. Every step is taken with care and consideration for the environment.

As I continue to learn from the master artisans and observe more artisans at work, I can’t help but reflect on the value of handmade goods. Yes, these products are often more expensive than mass-produced textiles, but witnessing the time, skill, and dedication that goes into each piece made me realize the value. Buying a hand-printed textile involves preserving a craft that is as much about cultural heritage as fashion and tradition.

Two artisans place freshly dyed indigo fabric in an open field to dry. With them handling the printed cloth, the intricate patterns on the sarees are revealed. If you look closely, you can see the result of the mud resist process. Photo Lizane Louw

Cultural and Economic Impact

Dabu printing is not just an art form; it’s a way of life for the people of Bagru. The designs are often drawn from the surroundings, tools, household objects, and the natural world. You can find floral motifs, geometric patterns, and symbolic representations of animals and plants. These motifs have been used for centuries, yet they remain timeless, connecting each piece of fabric to the region’s long history and people.

However, there is another side to print crafts: communities with countless challenges. On the upside, the global demand for sustainable fashion has brought new opportunities to the artisans and print communities in Rajasthan. The crafts are known, appreciated, and sold, but there are numerous and serious obstacles faced by these craft communities.

There’s a constant struggle in the region to maintain authenticity in the face of growing competition and the pressure to produce faster. There are movements away from traditional print crafts, more practice for profit, and the creation of questionable quality.

The question about the treatment of the craftspeople and the community’s well-being also comes into question; it is hard work and long hours behind print tables. One thing that is important for me when I set out on my textile print adventures is to research and note the material used to print and dye in studios. I think it is very important to research and to educate yourself on inks and dyes that are good for the workers to work with and also in the end, good for the environment.

What I discovered in Bagru is a community that is still dedicated to the old traditions of block printing and Bagru’s artisans remain committed to their craft, and their resilience is a testament to the strength of tradition in a rapidly changing world.

In the first picture you can view the rhythm of the print traditions continuing, uninterrupted at this open-air dyeing workshop in Bagru. Here, the fabric is not just dyed—it is transformed with patterns, pigments and prints, carrying the history of its makers. The indigo vat on the right showcase the real “alchemy” of natural colour. The artisans work with quiet focus, their clothes permanently stained by the deep blues of indigofera tinctoria, true indigo. Photo Lizane Louw

Embracing the Art of Slow Living

Every time I leave Bagru, I carry more than just the memory of my time there. I have a renewed appreciation for the value of slow living, of taking the time to create something meaningful, and, of course, bags and bags of printed textiles I printed myself. My growing collection of textiles, that I printed myself, makes me proud. I even launched my sustainable textile line, Mäya, in collaboration with Mud and Water, a small family-run print operation in Bagru. I have so many stories to share…

In our modern, fast-paced world that often values speed and convenience over quality and sustainability, my experience in Bagru reminded me of the beauty of handmade crafts and the deliberate and thoughtful process of creation. I learn so much from taking time out when I print; the process is like meditation. For me it is all about finding flow every time I print, even more so when I craft and paint with mud.

I am a Dabu printer, I love the resit printing crafts and I respect all the artisans I have met who practice this craft. As I continue to do my field research and to develop my practice, it is also important for me to understand the challenges and complications of the crafts. Most importantly, I want to share the stories of the craft and help everyone understand and appreciate the hard work of creating these beautiful mud cloths. I plan to continue to develop my skills in this craft and that I will find more inspiration to write more mud stories.

This textile journey with Bagru has changed how I think about my clothes and the items I bring into my home. I am learning with textiles and hand-printed crafts that each piece of printed fabric is not just a product; it’s a story of the land, the people, and the age-old techniques that bring it to life.

As consumers, we have the choice to choose these textiles, these stories, and the crafts. With this choice, we can support the artisans who keep these traditions alive and embrace a slower, more sustainable, earth-friendly way of living.

Supporting Sustainability

For those inspired to explore sustainability in textiles, I encourage you to consider the art of handmade textiles, the traditions of Dabu printing, Bagru printing, and all handweave traditions. Whether you visit Bagru and witness the process firsthand or seek out Dabu-printed textiles, you’ll support a craft embodying sustainability and cultural preservation. Look for pieces that carry the mark of authenticity—natural dyes and beautiful bold patterns created by nature. Dabu prints are raw, imperfect, rustic, and one of a kind. You can rest knowing that each Dabu print was made with care and respect for the environment. It is a way of life in the region.

The Future of Dabu Block Printing in Bagru

As I reflect on my time in Bagru and my love for Dabu printing, I can’t help but wonder what the future holds for this ancient mud craft. The world is changing rapidly; we live in a fast-paced world in high-tech societies. We seem to be moving faster; our world is becoming increasingly digital and mechanical. We are consuming and discarding more than ever before. With all this, traditional artisans face more and more challenges.

It is hard to adapt and adjust ways of working in the hand print crafts. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned on each taxi ride to Bagru and back, it is that the people of that village on the outskirts of the Thar desert are as resilient as the craft they practice. These skilled craftsmen have weathered centuries of change until now, and I believe they’ll continue to do so, adapting their practices in eco-friendly ways to meet the needs of the modern world while staying true to their roots.

Ultimately, my journies to Bagru was about more than just discovering new crafts—it was about finding a new way of seeing the world. I am excited to learn more about this mud craft that uses no chemical, industrial machine, or mechanical process, a craft practised with the elements and nature.

As Mr. Joshi, a textile merchant in Rishikesh whom I met one evening, told me with a big smile: “Indian textiles go deep. How deep will you go?”

I can’t wait to pack my bags and head to Bhuj and Kutch to learn more about the heritage textile crafts of this country, which I call my second home.

Additional resources: This section will be updated as my research continue.

Recommended print experiences:

Mud and Water and Bagru Printing workshop.

This is 4th generation award winning hand block printing workshop in the Chhipo ka Mohalia in Bagru. I did a four day printing exploration with Avinash, Akash and Mr. Digamber Medatwal. I was fortunate to experience a Bagru that very few people do. Avinash took me on electric scooter rides around the print workshops and went out of his way to share the operations of the studio and the work they produce. I also worked with this studio to produce the first print run of my first textiles designs I created with found blocks from their archive.

The family does not have a website, it is best to book with them directly, get in touch on Instagram. I highly recommend having a cup of chai with and also printing with Mr. Digamber Medatwal. What I learned from this master printer inspired a lifetime of research.

A very professional operation run by Anup Chhipa and his family – Anup is the Production Director at Studio Bagru

Anup is a fifth-generation block printer. He began printing at the age of 16 alongside his father and formally joined Studio Bagru in 2016. Anup is a master printer and also master of color. I witnessed this first hand. Anup oversees production management, retail operations, and printing workshops. I spend four days learning from Anup and the quality of the prints I created under the guidance of him and the team makes me very proud. I printed my first carpet with the guidance of Anup, I also got introcuded to pigment printing and shibori at this studio. I am also very lucky to have had the opportunity to also learn from his mom and dad. They make an incredible team, and I am very impressed with the quality of the print products I not only created, but also bought.

Recommended reading:

Gillow, J., & Barnard, N. (1991). Indian textiles. Thames & Hudson.

“Indian Textiles” by John Gillow and Nicholas Barnard explores the diverse textile traditions of India, covering the history, techniques, and cultural significance of weaving, dyeing, printing, and embroidery. Richly illustrated with good visual examples, the book highlights regional styles and the artistry of Indian textiles. This is a good starting point if you want to learn more about heritage textiles, textile arts and the Indian culture.

What not to miss in the area:

- Block Printing Workshops: Participate in hands-on block printing workshops offered by studios in Bagru or Jaipur; contact me for more information, I worked with a couple of family run operations and would love to share my experiences and suggestions with you. There are many.

- Visit the Anokhi Museum of Hand Printing: Explore textile exhibits showcasing the history and techniques of block printing. They also offer books for sale, and the books are very good for referencing sample fabrics and research, a must for every textile designer and researcher.

- Textile Shopping: Jaipur is not a village. It is more like a market, mall or giant bazaar; you can shop your heart out. Visit markets like Johari Bazaar, Bapu Bazaar, and Tripolia Bazaar for hand-printed textiles and other local arts and crafts. Shop around, but do some workshops first so that you know what you are buying.

- Shop Authentic Textiles in Bagru: Purchase authentic Bagru prints directly from the artisans and small studios in the village, support the local economy and take home unique, handcrafted textiles that can only be found in this village. They are truly one of a kind. I have a big growing collection that I printed myself and that I bought on my visits.

- Visit Anokhi in Jaipur: Don’t miss the chocolate and carrot cake at Anokhi Cafe in Jaipur. Have tea and cake after a great shopping experience at the Anokhi shop. Thank me later.

Photographs and text by

Lizane Louw

As a travel & culture journalist, Lizane researches, writes and shares original travel and culture-related stories. Lizane produces high-quality content for various platforms, including print, online, social media, and video platforms. Lizane enjoys writing feature articles, sharing experiential stories, and creating photo essays of all the offbeat, remote and interesting destinations she visits.